Throughout the remainder of the 1760s, British colonial governors struggled to maintain order as militias roamed the countryside, defending their homes and plantations against probing Indians and skirmishing with French forces, moving into New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine and Pennsylvania. Economic crisis hit the colonies in 1766 due to Britain’s inability to maintain protection of trade. Louis XV of France soon saw his opportunity to knock Britain out of the race for empire altogether and massed an army at Cherbourg for an invasion of Ireland.

American statesman Benjamin Franklin and others assembled again in Albany, New York, to discuss these circumstances and, in June 1767, a delegation of three Americans, including Franklin, were on their way to London to convince the government to allow the colonies to control their own affairs and to raise their own taxes. On April 16, 1768, the King put his signature to the Albany Plan of Union, granted that American merchant shipping to Britain could be protected by American ships and that they could raise armies by their own funds to protect themselves against the French. For the delegation, this would require support from all of the colonies, now the equivalents of independent nations.

The American Republic had come into existence even before King George III signed the Plan of Albany. On January 4, 1769, the handful of members of the Albany Congress who served the purposes of George Washington and the army resolved that "the people are, under God, the original of all just power...that the Congress of Colonies assembles, being chosen and representing the people, have the supreme power in this nation." On the 9th it was voted that the name of a single person should no longer be mentioned in legal transactions under the "American Seal." A new seal was presented, bearing on one side a map of the colonies and on the other a picture of the assembly building in Albany, with the inscription "In the first year of the freedom, by God's blessing restored." A statue of George III was thrown down in New York City, and on the pedestal were inscribed the words "Exit the tyrant, the last of the Kings." On February 5 it was declared that the colonial governors and the rule of Britain altogether "is useless and dangerous and ought to be abolished." Thereafter, Britain being powerless in the face of an aggressive France, the Royal governors were sent packing. Vengeance was wrought upon a number of lawyers and businessmen.

The former colonies were now to be governed by a Council of State chosen annually by Congress. Its forty-one members included landowners, judges, and lawyers, among them most of the principle enlightenment thinkers. It was found to be fearless, diligent, and incorruptible. The judiciary hung for a time in the balance. Six of the twelve judges refused to continue, but the rest, their oath of allegiance being formally abrogated, agreed to serve the State. The highly conservative elements at the head of the army held firmly to the maintenance of the English Common Law and the unbroken administration of justice in all non-political issues. The accession of the lawyers to the new regime was deemed essential for the defense of privilege and property against the assaults of extremists. This had now become the crucial issue. Fierce and furious as was the effort of the extremists, there was no hesitation among the men in power to put them down.

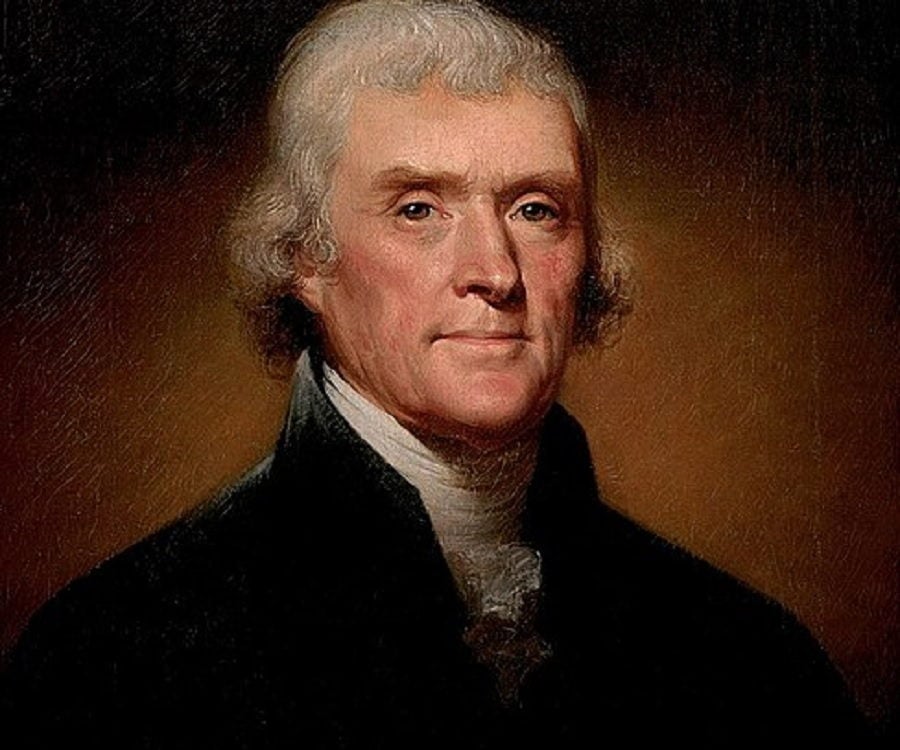

It was essential to divide and disperse the army, and George Washington was willing to lead the larger part of it to a war of retribution in the name of the Lord God against the idolatrous and bloodstained savage Indians. It was thought that an enterprise of this character would enlist the fanaticism of the rank and file. Lots were drawn which regiments should go to the wilderness, and were drawn again until only the regiments in which the extremists were strongest were cast. A pamphlet on America's Chains spread through the army. Mutinies broke out. Many hundreds of veteran soldiers appeared in bands in support of "the people," manhood suffrage, and annual Congresses. This mood was not confined to the soldiers. Behind these broad principles the idea of equal rights in property as well as in citizenship was broadly announced by a group led by Thomas Jefferson, which came to be known as "the Freemen."

Numbers of people appeared on the common lands in French-owned Ohio and prepared to cultivate them on a communal basis. These "Freemen" did not molest the enclosed lands, leaving them to be settled by whoever had the power to take them; but they claimed that the whole earth was a "common treasury" and that the common land should be for all. They argued further that the former British colonies traced their founding back to Christopher Columbus, with whom a crowd of settlers and adventurers had come to America, robbing by force the mass of the Indians of their ancient rights. Historically the claim was overlaid by centuries of custom and was itself highly disputable; but this was what they said. The rulers of the new republic regarded all this as dangerous and subversive nonsense.

No one was more shocked that Washington. He cared almost as much for private property as for Jefferson, but he cared more about the security of the new nation, which with the Jeffersonian settlements in Ohio, was threatening French attacks. "A nobleman, a gentleman, a yeoman," Washington said, "that is a good interest to the land and a great one." The Council of State chased the would-be cultivators out of Ohio, and hunted the mutinous officers and soldiers to death without mercy. Washington again quelled a mutiny in person, and by his orders, had Thomas Jefferson shot along the Ohio River. His opinions and his constancy have led some to crown him as "the first martyr of democracy." Washington also discharged from the army, without their arrears of pay, all men who would not volunteer for the Wilderness War. Nominated by the Council as Commander, he invested his mission not only with a martial but with a priestly aspect. He joined the Anglican divines in preaching a holy war upon the Indians, and made a religious progress to Winchester Episcopal in a coach drawn by six Flemish horses. All this was done as part of a profound calculated policy in the face of military and social dangers which, if not strangled, would have opened a new ferocious and measureless social war in America.

No comments:

Post a Comment